What is Summative Content Analysis in Qualitative Research? Step-by-Step Guide

What is qualitative summative content analysis?

Summative content analysis in qualitative research involves identifying essential keywords, counting occurrences across textual sources, and then reading them over to offer a final write-up.

Researchers use summative content analysis to explore large amounts of textual data for the usage of specific words and offer an analysis of their contextual meaning.

Summative analysis starts with the counting of pre-defined keywords before applying several iterations of manifest content analysis that are quantitative in the early stages. But the goal is to explore the usage of specific language through a deductive analytical approach.

To elaborate, you begin by choosing keywords and then count the number of times they appear in your textual data. Your initial manifest analysis records explicit frequency counts of key messages before defining and contextualizing the keywords in your write-up.

[Read: Qualitative Content Analysis: Manifest Content Analysis vs. Latent Content Analysis]

How is summative content analysis the same as other methods of content analysis?

Frequency is core

In content analysis, recurring keywords are considered a relevant way to extract meaning from data because they identify recurring concepts in your source material. These counts help you develop overarching themes in your data by influencing “the way key points are grouped and listed under developing topic-oriented headings” (Rapport, 2010).

Similarly, the first steps are the same in that you read—and reread—your source materials “using codes [or keywords] as a sense-making process” (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005) and count the occurrence of the words that elucidate key concepts in relation to the research questions.

While researchers cannot use statistical analysis alone to give meaning to data, they are able to assign relevance to quantitative data through qualitative content analysis. But the goal is to go beyond just counting words and examine language instead so that you are able to classify large amounts of text into an efficient number of categories with similar meanings.[2]

This is vastly different from all other methods of qualitative research. In grounded theory, thematic analysis, or phenomenological research—for example—frequency counts are considered irrelevant, and assigning value to them in your results is highly disparaged.

How is summative content analysis different from other methods of content analysis?

All qualitative content analysis aims to systematically summarize qualitative data (i.e. frequency counts) in a quantitative way. It is used to identify the intentions and trends of individuals, groups, or institutions within texts. However, each method of content analysis may lead to different results, conclusions, interpretations, and meanings.

Here are further distinctions between summative and other forms of content analysis:

Depth of analysis

Keywords in summative analysis describe how words are used and only seek to explain their context. In other methods of content analysis, you infer meaning from recurring keywords and messages in order to describe a larger—and often more fleshed-out—phenomenon.

Therefore, a fundamental difference between summative analysis and other methods of content analysis is that instead of analyzing data as a whole to describe a phenomenon, “the text is approached as single words or in relation to particular content” (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005).

[Find more helpful resources for learning qualitative data analysis in our Learning Center.]

Generating code and keywords

Some methods of qualitative content analysis use an inductive approach to generate keywords and code, while other methods rely on a more deductive approach.

For instance, you use an inductive approach in conventional content analysis and latent content analysis. An inductive approach is required because there are no preconceived codes or keywords. The theory or literature on the topic is limited and the aim is to fill that void.

Directed content analysis and manifest content analysis, on the other hand, use a deductive approach. Researchers rely on preexisting research to guide their analysis, coding scheme, and conclusion in order to add to current literature or theory on a topic.

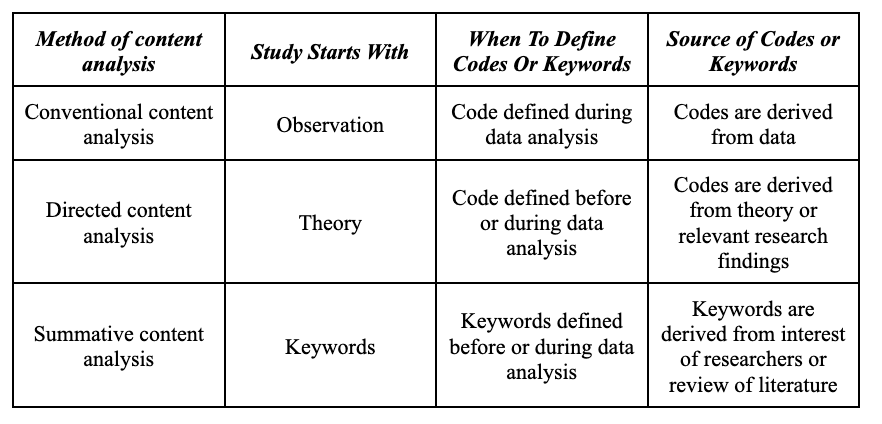

Summative analysis is also deductive in nature. However, while conventional content analysis begins with inductive observation and directed analysis with deductive theory, summative analysis begins with a manifest assessment of keywords—as shown in the table below.

You choose keywords only to contextualize and compare their usage across your textual data. The keywords you choose at this junction dictate the materials you will study, the coding scheme you apply, and the depth of analysis for your study.

The following table outlines how the research process begins with these three methods:

Focusing on usage

To piggyback from the previous section, Hsieh and Shannon add that summative analysis is more constrained by the keywords you initially create as “quantification is not an attempt to infer meaning but, rather, to explore usage.”

The goal is to examine the context associated with the use of the word or phrase in order to discover the range of meanings that they have in your textual source material.

Summative analysis provides an unobtrusive and nonreactive way to provide insights into how words are actually used in relation to a topic (Babbie, 1992). A nonreactive (at-a-distance) approach to data is especially helpful when studying topics that are sensitive or difficult to discuss—such as how mental health terminology is used across a large number of news articles.

But as summative content analysis keeps focus on explicit word usage, the results are also limited by the lack of attention given to implicit meanings that may exist in the text. Therefore, nuanced language like metaphors, slang, and similes may be misinterpreted or ignored in the same news articles—though they potentially provide insight into the topic of mental health.

Requiring content experts

In summative content analysis—content experts validate the rigor of your research process.

Validity is improved as experts help to identify the initial keywords used. They also ensure that all researchers understand how they apply to the specific topic being studied. Consultation with content experts is not requisite in other methods of content analysis.

For instance, you can identify keywords through focus group discussions with experts in the psychiatric field if you study a phenomenon related to mental health. Content experts also validate that the textual evidence is consistent with your interpretation in your final write-up.

Quoting the example study to follow:

“There are concerns that the keywords might have different connotations and understandings among mental health professionals and members of the public—including reporters. This potential setback was limited in the expert forum by involving a psychiatrist experienced in mass media psychiatric advocacy to generate the appropriate keywords.”

When should I use summative content analysis?

As the summative method only seeks to explore surface-level usage of keywords, it is a practical way to analyze large sets of data when there is far too much data to offer in-depth analysis.

With less time devoted to interpreting code and data, summative analysis is not only helpful to summarize large amounts of text faster but also to organize it into concise, logical results.

And as mentioned, summative analysis is especially useful when the topic you are studying is sensitive and evokes emotionally charged responses—both from researchers and their audience.

By examining only what’s apparent on the surface of the text, you “keep a distance” from any bias or personal opinions that may call into question the validity of your results.

To recap, you should consider using summative content analysis when you want to:

Understand the usage of specific words or content.

Navigate copious amounts of textual data to perform a study.

Explore the different meanings specific words can have.

Analyze sensitive, emotionally-charged subject matter.

Evaluate the quality of content in newspapers, journals, or other text materials.

What is an example of qualitative summative content analysis?

In this summative content analysis example—Mental illness portrayal in Media: A summative content analysis of Malaysian newspapers—Razali, Sanip, and Adawiyah Sa’ad investigated how four Malaysian newspapers reported on mental illness issues across 46 different news articles. The objective of the study was to contextualize how these newspapers use specific language relating to mental health.

The researcher’s step-by-step process of summative content analysis

1. Identify the keywords you want to study

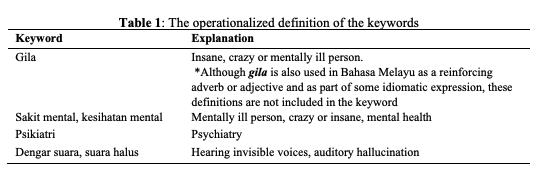

First, the research team held focus groups with mental health experts to come up with appropriate keywords to quantify in the news articles.

The keywords were “based on any Malay translation of English terminology for three main mental health disorders: schizophrenia, bipolar mood disorder, and major depressive disorder.”

The existence of keywords was one of the two main criteria for how the researchers selected the 46 news articles studied. Specific mental health-related keywords included ‘gila’, ‘sakit mental’, ‘psikiatri’, and ‘dengar suara’ and ‘surara halas’.

The second criterion was any article that “predominantly related to psychiatry”. Whether or not the article was intended for entertainment or educational purposes was irrelevant.

2. Look for the occurrence of the keywords

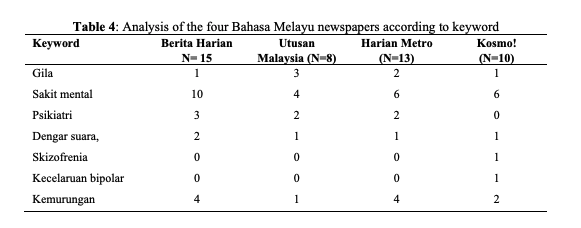

Next, the researchers counted the number of times these keywords appeared throughout the 46 articles. The most prevalent term was ‘sakit mental’, which appeared 26 times. The total occurrence of each keyword across the four newspapers (Berita Harian, Utusan Malaysia, Harian Metro, Kosmo!) was tabulated in the following table.

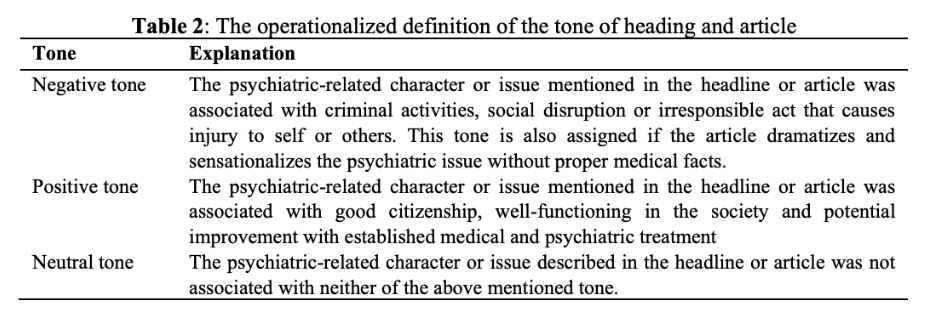

At this stage, the researchers also applied sentiment coding to compare how the newspapers depicted issues of mental health. They examined if the headline and body of each article used a negative, positive, or neutral tone to portray people with mental health disorders—or the tone of language used to refer to this group.

The researchers offered operationalized definitions of each code:

The sentiment codes did not apply directly to the keywords. However, the recurring use of words like ‘gila’ (insane, crazy, mentally ill) throughout the articles helped the researchers “quantify the frequency of negative versus positive depictions of mental illness patients” in their write-up. This was the goal stated in the study’s introduction.

How can I streamline data collection & collation?

Both parts of this step could be done by hand or with the help of QDA (qualitative data analysis) software like Delve. Delve’s search feature allows you to quickly search your textual data and instantly tells you the frequency at which each keyword appears.

You can even select specific sets of keywords, export the information into Excel, and organize or edit the data as you proceed. And from within Excel, you can then easily visualize your frequency counts into graphs tables, or charts for your write-up.

3. Identify the frequency of alternative keywords

Now, you should count the number of times alternative keywords appear in data. Alternative keywords are not necessary to include but can be added to your keyword list at this stage. All qualitative methods of research are an iterative process and alternative keywords help ensure valuable data is not overlooked.

Though the researchers may have added recurring mental health-related keywords they discovered within the articles at this stage, no alternative keywords were added in this particular study. If the researchers did decide to add alternative keywords or amend the keyword list, the expert panel would need to validate each change.

While not included in their data, the researchers did conclude that additional keywords such as ‘tidak waras’, ‘sewel’, saki otak’, and ‘sakit jiwa’—all different Malay terms that roughly translate to “crazy” or “madness”—would have improved the rigor of their study.

4. Analyze and compare data

Next, the researchers analyzed and compared their findings. After analyzing the quantified data, “a comparison was made among the newspapers in regard to the tone of the headlines and the articles and the existence of experts’ opinions within each article.”

The researchers compared the data and found:

“None of the articles were written by any professional working in the clinical field of mental health. The majority of the articles (87%) did not cite any onion from professionals in the field.” Authorship and expert opinions were considered to inform readers whether the articles and headlines were written by mental health experts.

According to the researchers, articles written by journalists without consulting any expert opinions on mental health suggest that one should call the validity of those articles into question. This suggests that most of the articles only provide superficial, uninformed representations of mental health.

5. Write your narrative and offer suggestions for future studies.

As mentioned, the researcher’s goal of the study was to “quantify the frequency of negative versus positive depictions of mental illness patients” in four Malay newspapers.

Their write-up tabulated the different usage of the keywords and compared their meaning.

By analyzing the frequency counts, the team concluded that:

“Negative views were overrepresented in the news media when mental illness is reported. Patient or characters with the psychiatric disorder was significantly more frequently associated with dangerousness, criminal activities, unpredictability, and dysfunction.”

The conclusion also offers more suggestions to decrease the stigmatization of mental health representations in Malaysian mass media. For instance, they suggest that psychiatrists and clinical psychologists should come forward more often to appear in broadcast media or to write professional articles about mental health for the public.

The best software for summative qualitative content analysis

With Delve’s qualitative content analysis tool, code counts are instantaneous and easily searchable within the simple user interface. The time-saving elements of these features are especially helpful when combing through large amounts of textual data.

Advanced code frequency & co-occurrence matrices—with Delve

Delve also provides advanced code frequency through code co-occurrence matrices. These matrices show how frequently codes overlap, and how codes correlate to descriptors or attributes you identify. When considering alternative keywords for your summative analysis, this is another feature that reduces the heavy lifting of sifting through mountains of hand-coded material.

Cloud-based, collaborative, and cost-effective

Delve is cloud-based, collaborative, cost-effective, and easy to learn. It includes free tutorial videos, responsive customer support, and flexible payment options. Start your free trial today.

Not convinced? As researchers ourselves, we understand the pitfalls of most CAQDAS software. See why researchers like Tamra are switching to our easy-to-use, drag-and-drop coding software.

References

Krippendorff, Klaus. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Fourth Edition, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2019.

Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Rapport, F. (2010). Summative Analysis: A Qualitative Method for Social Science and Health Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 9(3), 270–290.

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

Babbie, E. (1992). The practice of social research. New York: Macmillan.

Razali, Zul & Sanip, Suhaila & Saad, Rabiatul. (2018). MENTAL ILLNESS PORTRAYAL IN MEDIA: A SUMMATIVE CONTENT ANALYSIS OF MALAYSIAN NEWSPAPERS. International Journal of Business and Society. 19. 324-331.

Cite this blog post:

Delve, Ho, L., & Limpaecher, A. (2023c, February 4). What is summative content analysis in qualitative research? https://delvetool.com/blog/what-is-qualitative-summative-content-analysis